The Junior Thesis is one of GCDS’s signature programs, housed within the Grade 11 Seminar course taken by every Junior. Building on skills built in Grades 9 and 10, students apply their learning to produce a meaningful academic project—a piece of solidly researched, polished prose written in stages over a period of months—proposed in the fall and defended in the spring. The Junior Thesis Program engages the entire faculty, whether as Seminar teachers, thesis advisors, or third readers, and as such stitches the school together in a shared institutional enterprise. The experience has become an important milestone in a GCDS education.

Chloe Caliboso

The Math Behind Rubik’s Cube Solving and the Superiority of the Fridrich Method

Chloe Caliboso picked up cubing during the pandemic. “I was obsessed with the Rubik’s Cube and got down to 24 seconds as my record.” Chloe started playing with it again around the time she had to choose her Junior Thesis topic. “I thought to myself, I love cubing and want to know more. Let me dive into this.”

Chloe, who is pursuing a GCDS engineering diploma, knew that she wanted to focus on a topic related to math or computer science. She will be taking CSX, an advanced computer science class next year, and also loves painting and the arts. “I wanted to work on something both STEM-related and aesthetically pleasing.”

Chloe met with her thesis advisor, Upper School Math Teacher Andrew Dutcher, every week. “Learning how to talk about math was one of the hardest things I had to do,” she said

For at least the first four meetings, Chloe said that she left the meetings confused. Nonetheless, she persisted with Mr. Dutcher for possible paths forward. Mr. Dutcher gave her math rid-dles to help focus her. “With puzzles and math, you have to really think a certain way in order to fully understand the intersectionality,” she explained.

Chloe researched how mathematicians calculated that there were 43 quintillion possible permutations of the Rubik’s Cube. From there, she calculated the algorithmic reduction to figure out which of the three main methods solves the game the fastest. In doing so, she learned that the most popular method, the Fridrich method or the CFOP method, is not the fastest method.

Chloe concluded that “just because something is algorithmically the fastest, it doesn’t necessarily mean that it is the most popular or efficient method.”

Chloe didn’t know anything about Jessica Fridrich, the founder of the CFOP method and a professor of Electrical and Computer Engineering at SUNY

Binghamton University, who is also a fine artist, before her research. “I really fell in love with her story and how her method brought popularity back to the Rubik’s cube,” she recalled.

“I think if you choose something that you really enjoy but don’t know that much about, this is going to be a really great journey for you,” said Chloe about her Junior Thesis. “You’re going to have a lot of fun. That’s what had happened to me.”

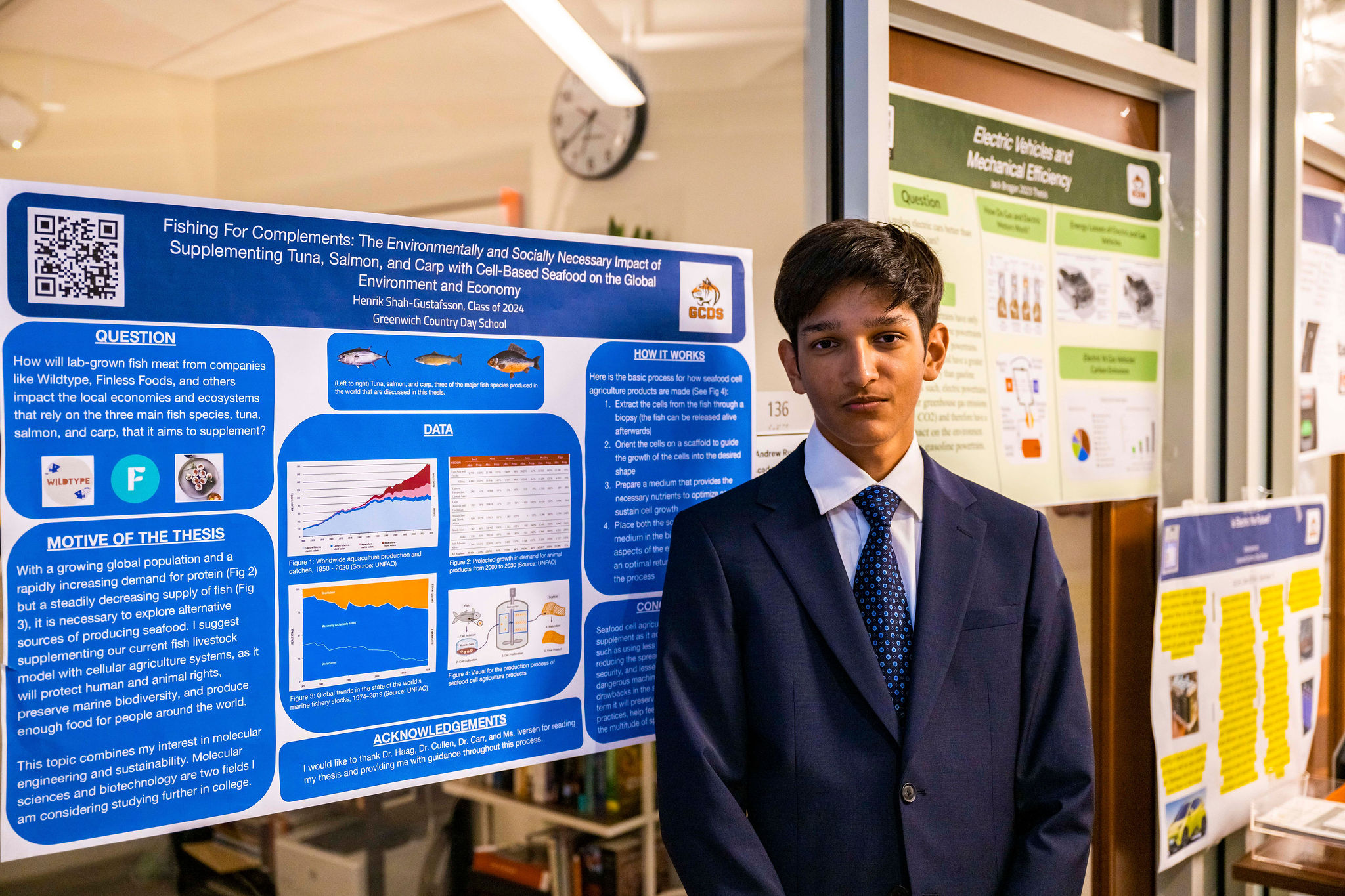

Henrik Shah-Gustafsson

Fishing For Complements: The Environmentally and Socially Necessary Impact of Supplementing Tuna, Salmon, and Carp with Cell-Based Seafood on the Global Environment and Economy

Henrik Shah-Gustafsson sees a future with a transformed fishing industry. Last spring, he and his mother had been talking about a burgeoning new field of cellular agriculture. As a student interested in biology and chemistry, this new technology piqued Henrik’s interest as a Junior Thesis topic.

Cellular agriculture is the process of using bio-engineering and cell develop-ment techniques to produce food items, in particular fats and proteins, explained Henrik.

Upper School Biology Teacher Nathan Haag served as Henrik’s advisor and encouraged the pursuit of this topic. However, Dr. Haag pushed Henrik on specificity. “I shifted from cellular agri-culture as a whole field, to the production of three types of fish—tuna, salmon and carp,” he said.

His thesis focused on the potential impact of cellular agriculture for these three fish on local economies and eco-systems. It dealt with the technology’s theoretical application, but also explored the developing scientific processes that exist currently.

“There are multiple problems with fish farming and traditional fishing, such as pollution and animal rights,” said Henrik.

“There’s an increase in population, an increase in protein demand, but a decreasing stock in fish,” said Henrik, who is pursuing an engineering diploma. “Cellular agriculture could be a promising technology to produce food sustainably,” he said.

The new technology will have a mul-titude of benefits, such as reduced resource usage and health benefits for humans, explained Henrik. “In order to feed 10 billion people, we have to look for new solutions.”

Aside from their regular meetings, Henrik would reach out to Dr. Haag anytime he wanted to talk through an idea or problem. “I would just send him a message and we would meet to discuss my ideas and obstacles,” he said.

Prior to the Junior Thesis, Henrik had never written a 12-page paper before. He admits that initially the writing process was challenging. “I had to overcome the idea of the length of the paper,” he explained.

Although it has been almost a year of researching cellular agriculture, Henrik is not tired of the subject matter and, in fact, wants to continue studying the topic. “Since it’s a new field, there’s always something interesting to learn. I want to further my knowledge.”

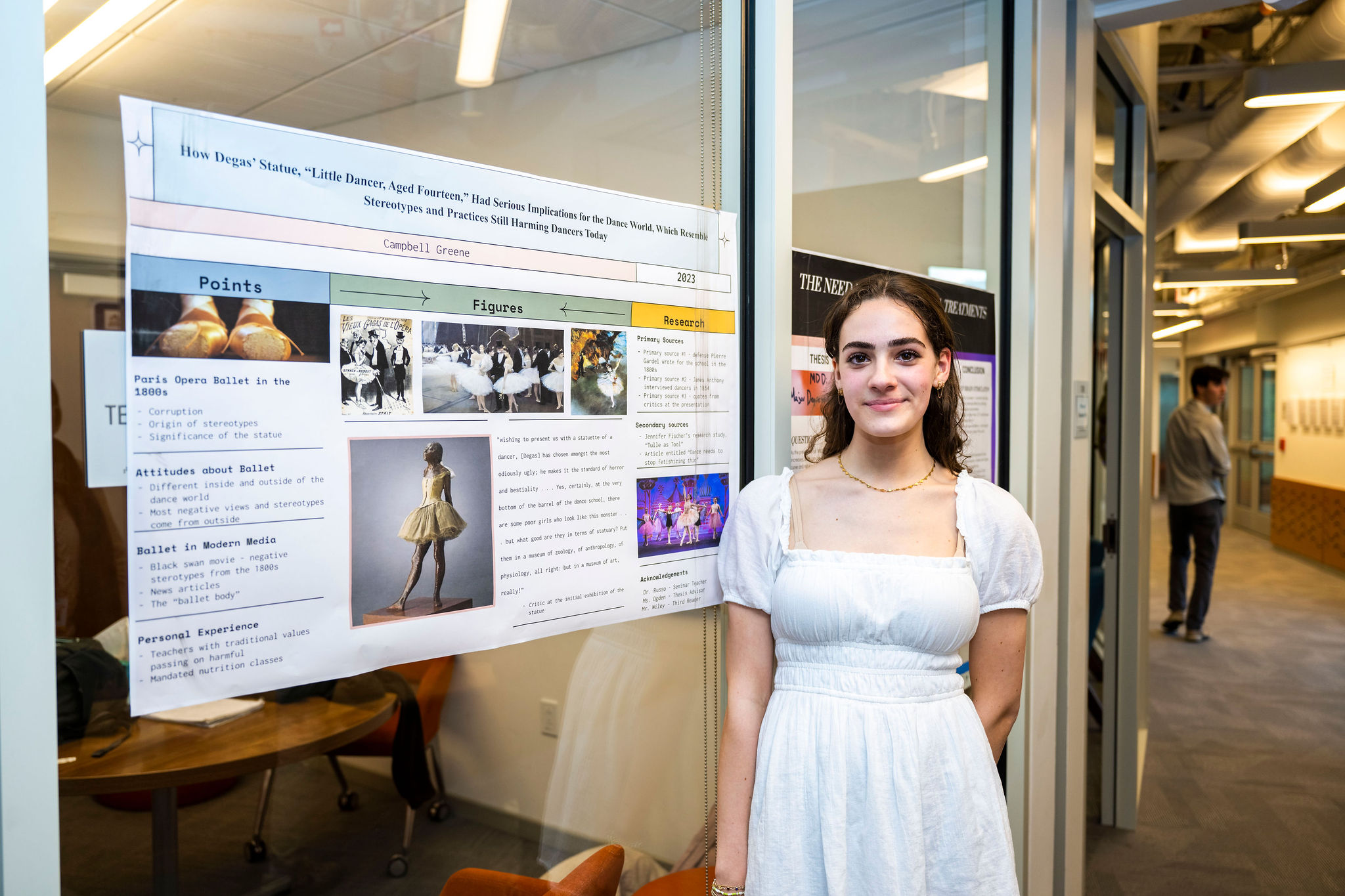

Campbell Green

How Degas’ Statue, “Little Dancer, Aged Fourteen,” Had Serious Implications for the Dance World, Which Resemble Stereotypes and Practices Still Harming Dancers Today

Campbell Green not only dances ballet, but she also wants to understand the history and psychology of ballerinas, past and present.

Over the years, Campbell has danced with ballet companies and has noticed that people have negative stereotypes of dancers around eating disorders and body image. “I wanted to know where these stereotypes came from.”

As she began to dive deeper into the subject of women’s mental health in ballet for a Junior Thesis topic, she learned about Degas’ iconic sculpture of the 14-year-old ballet dancer. “It sparked my interest about what it must have been like to be a ballerina in the 1800s.”

Campbell learned about the history of the Paris Opera and creation of the dance program. Originally, the ballet was geared toward wealthy male subscribers who would become patrons of their favorite dancers, funding their housing, education, and careers.

At the time, parts of French society had an unfavorable view of ballerinas because of their association with prosti-tution. “These ballet girls often had no choice because they were impoverished and were dancing as a job to support their families,” said Campbell.

At the age of 14, it was decided whether a girl had a “ballet body,” explained Campbell. Degas befriended dancers like Marie van Goethem, the subject of his sculpture, and represented them naturally, as opposed to pictures of perfection. “He drew them as real people, not through a stereotypical male gaze. That was unorthodox at the time—and even radical.”

Campbell divided her thesis into two parts. The first part tackled the history of the Paris Opera and the second looked at modern media. She wrote about Black Swan, a 2010 psychological thriller starring Natalie Portman, who struggles with perfectionism and an eating disorder, and deals with sexual harassment. “In a way, the film mirrors the 1800s.”

“Ballet has been seen as something that didn’t empower women,” said Campbell. However, she cites more mod-ern research and attitudes that counter the narratives of the past. Ballet is con-sidered a respectable form of high art and patrons have genuine appreciation for the dancers’ talent. Campbell found studies that show that many ballerinas today are “empowered” by their art.

Campbell, who worked closely with her thesis advisor Annie Ogden ’14, Upper School English Teacher, and her Seminar teacher Paula Russo, enjoyed every aspect of the Junior Thesis. “I found it easy to write because I picked a topic that I’m passionate about and very vested in.”

.JPG&command_2=resize&height_2=85)

.jpg&command_2=resize&height_2=85)